Welcome to the BEAM Blog!

Happy Pi Day from BEAM!

WHAT DO YOU KNOW ABOUT PI?

Maybe you would say it’s a handy constant, helpful when trying to figure out a circumference or area. Maybe you’d say it’s irrational and transcendental. Maybe you’d say you know the first five digits, 3.1415 (or maybe you even know the first 10 or 15 or more). But whether you know the first 5 or the first 5000 digits, there are a lot of questions we can ask about the digits that make up pi.

We could wonder about whether a specific string of digits (such as your birthday) exists somewhere in pi or even if all possible finite strings of digits appear somewhere in pi.

What do you know about pi?

Maybe you would say it’s a handy constant, helpful when trying to figure out a circumference or area. Maybe you’d say it’s irrational and transcendental. Maybe you’d say you know the first five digits, 3.1415 (or maybe you even know the first 10 or 15 or more). But whether you know the first 5 or the first 5000 digits, there are a lot of questions we can ask about the digits that make up pi.

We could wonder about whether a specific string of digits (such as your birthday) exists somewhere in pi or even if all possible finite strings of digits appear somewhere in pi.

The first 100 digits of pi have plenty of birthdays!

Happy birthday to everyone celebrating their birthday on pi day! Your birthday is underlined. We also found Leonhard Euler’s birthday, April 15, and highlighted it in green.

Mathematician Emmy Noether’s birthday, March 23, is also in pi! We highlighted it in purple.

Looking deeper into pi’s digits, we noticed mathematician Alberto Calderón’s birthday (September 14, 1920) in the 295-7th digits of pi, highlighted in yellow:

Even later in the sequence of pi, we even found mathematician Benjamin Banneker’s birthday (November 9, 1731) in the 3254-7th digits of pi, highlighted in blue:

The first 1000 digits of pi are here if you want to look for your birthday!

You could also ask what seems like a simple question: does the digit 7 appear infinitely often in pi? Probably yes, right? Would you expect 5's to show up more or less often than 7's, or equally often? Do you expect each digit to show up 1/10th of the time?

Amazingly, we don't know the answer to those questions, not for sure, anyway.

All these questions have to do with the sequence of digits that makes up this famous constant, and it turns out that, despite its fame, there’s still a lot to learn about the digit distribution of pi. The answers are wrapped up in mathematical concepts called normality and simple normality. In mathematics, simply normal means every digit appears equally often as we go out to infinity, and normal means that every possible finite string of digits appears equally often as we go out to infinity. To make this more formal a number is simply normal in an integer base b if its infinite sequence of digits is distributed uniformly in the sense that each of the b digit values has the same natural density 1/b. A number is said to be normal in base b if, for every positive integer n, all possible strings n digits long have density 1/bn.

All these questions have to do with the sequence of digits that makes up this famous constant, and it turns out that, despite its fame, there’s still a lot to learn about the digit distribution of pi. The answers are wrapped up in mathematical concepts called normality and simple normality. In mathematics, simply normal means every digit appears equally often as we go out to infinity, and normal means that every possible finite string of digits appears equally often as we go out to infinity. To make this more formal, a number is simply normal in an integer base b if its infinite sequence of digits is distributed uniformly in the sense that each of the b digit values has the same natural density 1/b. A number is said to be normal in base b if, for every positive integer n, all possible strings n digits long have density 1/b^n.

As an example, the number 0.12345678901234567890123… (where we just repeat all ten digits in consecutive order) is simply normal, but not normal. Each digit appears equally often as we go out to infinity, but the string 11 never appears!

To get a better picture of how the digit distribution looks for pi in particular, we have color coded the digits and plotted the digit distribution for the first 10, then 100, 1000, and finally 10,000 digits of 𝛑. We see as the number of digits we are looking at increases, the slices start to look more similar in size. If this holds true as we head out to infinity then that would mean that pi is simply normal in base 10.

When thinking about math, it is often helpful to think about statements in terms of stronger or weaker. Stronger statements give us more information, but they are also harder to prove, while weaker statements are easier to prove but don’t tell us as much about the subject or topic we are interested in. You will notice that saying a number is normal gives us a lot more information about its digit distribution than simply normal does. Normality tells us something about how often all possible finite strings appear, instead of just how often each digit occurs. That’s a lot more information!

If every possible finite string occurs at least once, well then we can certainly find our birthday. We can find everyone’s birthday. We could find the whole works of Shakespeare encoded in pi — or any book ever written for that matter. Normality even implies that all finite information is encoded in a normal number. What’s more, if a number is normal, then it will automatically be simply normal, and if a number is simply normal then it has to have infinitely many of each digit.

However this is where our wild wondering about what can be found encoded in pi comes to an abrupt disruption. It turns out that it has yet to be shown that there’s even infinitely many 7’s in pi, much less whether it is simply normal or, beyond that, normal.

So why do we think it’s normal anyway?

When we zoom in on a specific number like pi, it can be hard to show anything about its normality. However, zooming out and looking at the whole set of normal numbers and the whole set of non-normal numbers, mathematicians CAN prove things about these sets and we can even try to measure these sets. The mathematical machinery that we use to try to measure sets is called (maybe you guessed it) measure theory. While we don’t have time to go into how we measure a set like normal or non-normal numbers, it turns out that the set of numbers that are NOT-normal has “measure 0.” (Itching to see an actual proof of this fact? Don’t worry, just jump to the further reading section at the end of this post.) Intuitively this means that almost every real number is normal, because when we measure the set of numbers that are not normal it’s vanishingly small (measure 0). Since almost all numbers are normal, and we have no special reason to think pi would not be normal, we can guess that it probably is.

All that’s to say, as special and unique as pi is, it’s likely that it’s just a normal number like (almost all of) the rest of them.

While it would be nice to settle the question more definitively, the unknown is part of the joy and frustration that comes with thinking about open problems, problems without any known solution. Sometimes the lines between the known and unknown appear in unexpected places. The frontier of mathematics is not a smooth, well defined arc, but rather a wild, craggy expanse. Even when it comes to pi, there’s still much more to explore.

Further Reading:

If you still have room for more musings about numbers here is a great Numberphile video that goes over different types of numbers and includes a nice discussion on normal numbers (starts right about the 8:15 mark). It’s also helpful to see where normal fits in with other properties we may be better acquainted with such as rational/irrational, or transcendental:

And finally for those wanting to check out an actual proof of the fact that non-normal numbers have measure 0 here are a couple options:

If you have a working knowledge of measure theory under your belt here is a proof for the fact that non-normal numbers have measure.

Or if you are a math undergrad student and haven’t seen measure theory yet, but have an understanding of calculus, here is a neat approach that tackles proving the same fact without measure theory; instead you’ll just need some knowledge of sequences and series, as well as how to integrate step functions on an interval.

Looking for the solution to the Pi Day Math Problem?

Check out this blog post!

Happy Pi Day!

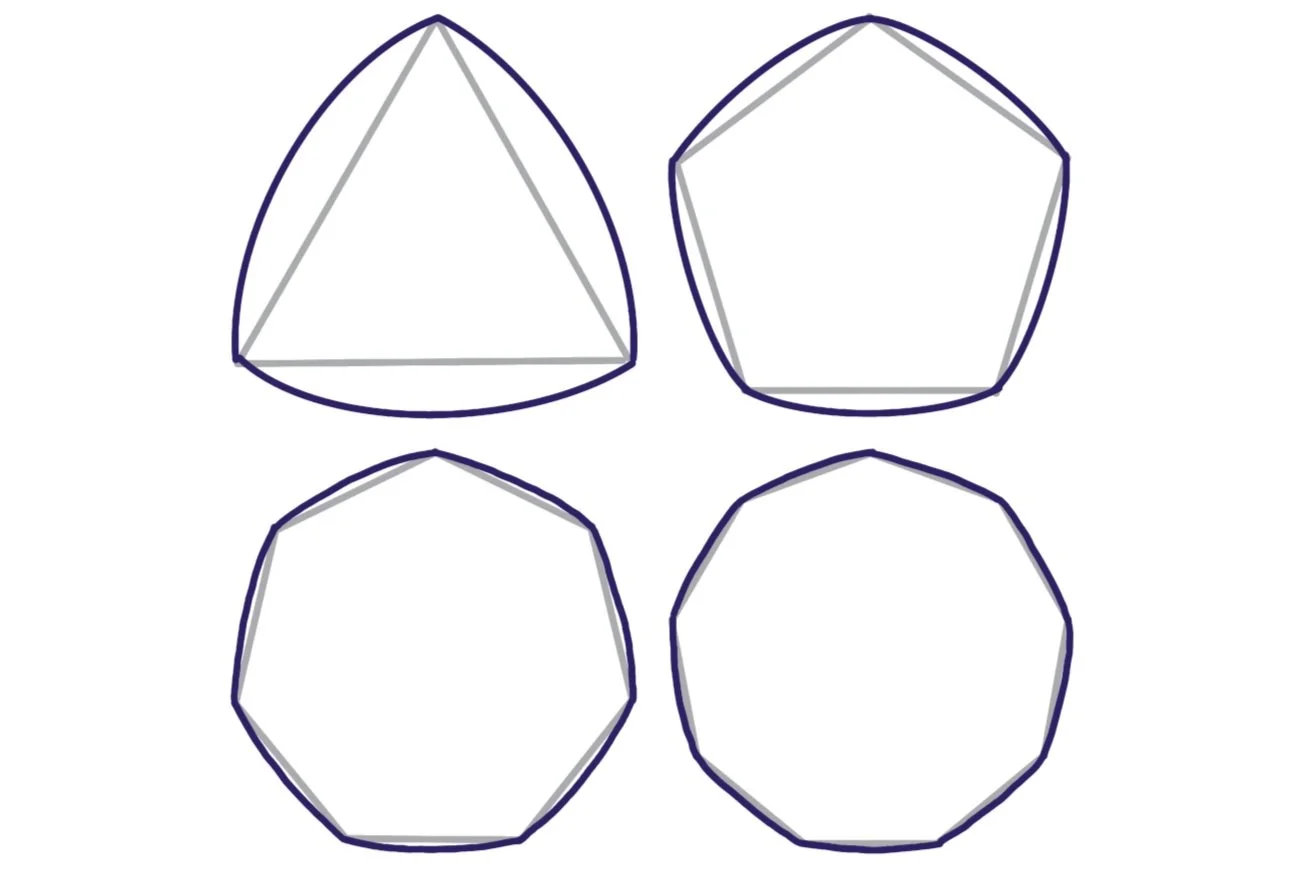

Happy 𝝅 Day! We’re celebrating with Reuleaux polygons and the remarkable property that ties them to 𝝅. We’ll also take a look at some of the many applications of these interesting shapes, touch on some big mathematical results, and even share a few open questions in the world of Reuleaux polygons!

Happy 𝝅 Day! We’re celebrating with Reuleaux polygons and the remarkable property that ties them to 𝝅. We’ll also take a look at some of the many applications of these interesting shapes, touch on some big mathematical results, and even share a few open questions in the world of Reuleaux polygons!

Reuleaux Polygons and 𝝅

A Reuleaux triangle is a "curve of constant width." That just means that whenever you hug them with two parallel lines, they're always the same width apart:

Because of that, you could use them as wheels or in a whole bunch of other places where you might "normally" use a circle (or where circles won't do, like a drill that makes square holes). More on that below!

You can build a Reuleaux triangle by taking three intersecting circular discs, each with its center on the boundary of the other two, like this:

Alternatively, you can think of it as an equilateral triangle where each side of the triangle has been replaced with a circular arc whose center is on the opposite vertex.

But, it’s not only triangles! There are infinitely many Reuleaux polygons which we can build in a similar way. Start with any regular polygon with an odd number of sides, replace each edge with a circular arc whose center is on the opposite vertex, and voila — you have yourself another Reuleaux polygon!

So what about this connection to 𝝅? Well, it’s not too different from a circle’s. You probably know the formula for finding the circumference of a circle:

c = πd

Divide by d to get c/d= π. This gives us a fundamental property of circles: when you divide the length around by the diameter, you always get π no matter the size of the circle.

For a Reuleaux triangle, we refer to the perimeter p instead of the circumference, and we talk about the width w instead of the diameter. (These are just different names for the same concepts.) To find the perimeter, notice that the angle at the vertex of an equilateral triangle is 60 degrees. Then the arc on the opposite side of the triangle is 1/6 of the way around a circle with a radius of w. Because the whole circumference would be 2wπ, that means that the length of that arc is:

2wπ/6 = (π/3)w

Add up all three arcs that make the Reuleax triangle, and you get πw for its perimeter.

Divide that by the width, and we find that:

p/w = πw/w = π

This means that, amazingly, Reuleaux triangles have the same relationship with π that a circle has! In fact, the same calculation works if we start with ANY regular n-gon where n is odd, so really this relationship holds for ALL Reuleaux polygons. (Read on to discover an even bigger generalization of this result.)

Applications

The fact that Reuleaux polygons are curves of constant width makes them popular for use in various settings. Since they roll nicely, coins that are the shape of a Reuleaux polygon can still be used in vending machines! Some examples include the Canadian Loonie (a Reuleaux 11-gon) and the 2 pula coin from Botswana (a Reuleaux 7-gon).

Like with the commonly used circular manhole covers, the constant width of Reuleaux polygons means that with just a small lip underneath, they can’t fall into the holes that they are made to cover.

Photo by Owen Byrne

So why aren’t they commonly used as manhole covers? Well, if you need to roll them on their side, the center of gravity makes them harder to roll… But that’s exactly the property that makes them desirable for making pencils with a Reuleaux cross-section. These ones will be less likely to roll off your desk.

Similarly, a fire hydrant valve in the shape of a Reuleaux triangle can be helpful in preventing mischief, since you’ll need a special tool to get it open.

Spot the Reuleaux triangle bolt head?

Reuleaux triangles also have a really cool relationship to squares! They can form a rotor within a square, that is, they do a full rotation inside the square while maintaining contact with all four sides.

In the early 1900’s, the Watt’s Brothers Tool Works used this relationship to patent a drill bit that can drill square holes! You can view the original patent!

And if you’re wondering where these shapes get their name, it comes from Franz Reuleaux (1829-1905), the German mechanical engineer who studied and designed mechanisms that convert rotation around a fixed axis into a back-and-forth or up-and-down motion. One of the possible applications is a film advance mechanism, like the one seen here:

Bigger Math Results and Open Questions

Barbier’s Theorem, first published in 1860, showed that every curve of constant width has the same relationship to what we’re celebrating today, namely, p/w= π.

Wondering about the area of a Reuleaux triangle? It’s known to be 1/2(π-√3)w2. If you’d like to try deriving it yourself, you might consider breaking it into an inner equilateral triangle and the three curvilinear regions formed between this triangle and the circular arcs.

The Blaschke–Lebesgue Theorem proves that the Reuleaux triangle has the smallest area of all curves of a fixed constant width.

And if you’re looking for open questions…

The optimal packing density of Reuleaux triangles in the plane is conjectured but unproven!

In 3-dimensions, it’s unknown which surfaces of constant width have the smallest volume!

Or maybe you’d just like to see some surfaces of constant width in action — check out this cool video from Numberphile!

Happy 𝜋 Day!

Happy 𝛑 Day! What better day to celebrate our favorite, familiar, fantastic irrational number? This 𝛑 Day we are bringing you a 𝛑-centric approximation activity, a detailed explanation of why this activity approximates 𝛑, and a special bonus math problem and solution (in case you want to spend your 𝛑 Day doing math, math, and more math :) ).

Happy 𝛑 Day! What better day to celebrate our favorite, familiar, fantastic irrational number? This 𝛑 Day we are bringing you a 𝛑-centric approximation activity, a detailed explanation of why this activity approximates 𝛑, and a special bonus math problem and solution (in case you want to spend your 𝛑 Day doing math, math, and more math :) ).

First, the activity:

Select your favorite straight thin object you don’t mind tossing at random. For example: birthday candles, crayons, toothpicks, Q-tips, etc. The more the merrier.* Whatever you pick, you want them all to be about the same length. We will use birthday candles for our example.

Make parallel lines on a flat surface. Make the distance between the lines twice as far as your throwing object is long. So, for birthday candles, your lines should be two candle lengths apart. To make lines you can use masking tape or Sharpie on butcher paper.

Now toss all your throwing objects onto the flat, lined surface. Carefully count how many objects cross a line. Now divide the number of objects you tossed by how many crossed one of the lines. Does this ratio look familiar?

*If you don’t have 100 or more of your tossing objects you may wish to do the experiment multiple times using fewer objects. Just keep a tally of the total number of objects you have tossed and the total number that have crossed a line. And use your tossing object tally and crossing tally to find the ratio at the end.

Why in the world does this work?

First, let's think about our set-up. The lines are two tossing objects apart so from here on our we will just use the length of our tossing object as our units. In our case we were tossing birthday candles, so for our calculations and graphs 1 unit = 1 candle length. Okay, now let's get into calculations. To simplify the problem we’ll start by thinking about just one of our candles, and see if we can work out the probability that it should cross a line when tossed randomly.

Zooming in on just one of our candles we have the following situation. (We included the two candles along the edge just as a reminder that the lines are 2 units apart).

Examining this picture we see that there are two variables, the angle at which the candle falls, θ, and the distance from the center of the candle to the closest line, D. Theta can vary from 0 to 𝛑 degrees and is measured against a line parallel to the lines in the experiment. The distance from the center of the candle to the closest line can never be more than half the distance between the lines, which means D ≤ 1 unit.

The candle in the picture misses the line. We know that candle will hit the line if the closest distance to a line (D) is less than or equal to the length of the dotted line, L. Thanks to trigonometry, we can find the length of this dotted line in terms of θ, and it is ½ (sin(θ)), so L is a function of θ, and we can write L(θ) = ½ sin(θ). If you aren’t familiar with trig functions yet, hang in there, you can still follow most of this! You just have to take our word on the graph of L(θ).)

In the graph below, we plot D along the y-axis and L(θ) along the x-axis. The values on or below the curve represent a hit, namely D ≤ L. The chances that we will hit the line are given by taking the area below the curve (that is the area of values of D and L that yield a hit) and dividing it by the area of the rectangle that represents all possible values for D and L (this rectangle is shown with the dotted green lines).

The area of the rectangle is of course easy to find and it is just 𝛑. The area of the shaded region does require some calculus to find and it is given by the definite integral of L(θ) evaluated from 0 to 𝛑, which comes out to just 1. Which means that the chances a value of (D,θ) randomly chosen fall within the shaded area are 1/𝛑. Which is the same as saying that the chances we hit the line on any given throw are 1/𝛑. That means that if we threw as many candles as we could randomly, about 1/𝛑 of them should hit the line. So:

Which means:

So there we have it, our famous and familiar ratio, 𝛑, showing up in an unusual and unexpected place. This explanation was largely based on this handy overview and explanation of Buffon’s needle problems: https://mste.illinois.edu/activity/buffon/. It also includes a simulation, which is the less messy option for trying this experiment if you don’t have a looooot of tossing objects at home.

And if you’d like to celebrate 𝛑 Day with a little extra math, try out the challenge problem below. (The answer appears after the problem.)

Following BEAM Discovery (our summer program for rising 7th graders), students are sent monthly Challenge Sets, fun math puzzles that students can do independently (and win prizes!). This is a math problem from the first Challenge Set of this school year. (It comes from the Math Kangaroo Contest.)

Myriam chooses a 5-digit whole number, and deletes one of the digits to make a 4-digit number. When she adds the 5-digit and 4-digit numbers together, she gets 52713.

What is the original 5-digit number?

Solution:

Let’s use A, B, C, D, and E to represent the digits of our 5-digit number, where A, B, C, D, E are all whole numbers from 0 to 9. So our 5-digit number looks like ABCDE. If this is the case, then we have 5 options for our 4-digit number: ABCD, ABCE, ABDE, ACDE, and BCDE. You might notice that four of these options end in the same digit as our original 5-digit number, namely E.

Well, what happens when we add two numbers that end in the same digit? In the ones place of our new number we will get the ones digit of E + E = 2E. We know that 2E must be an even number, so its ones digit is 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8. But we are looking for a ones digit of 3, because our 5-digit number and 4-digit number need to sum to 52713. That means we know that we don't want our 4-digit number to end in E. So, in fact, ABCE, ABDE, ACDE, and BCDE aren’t options.

Note: We interrupt our original post to provide an alternate (and really lovely) solution suggested by a BEAM supporter:

Now that we know the last digit is the one that must be dropped, we have an approximate equation X + X/10 ~ 52713. Solving this equation gives X ~ 47920.9090..., from which we can immediately deduce that A = 4, B = 7, C = 9, and D = 2, and very likely E = 1. Testing shows that this is indeed the solution, making short work of this problem!

This clever alternate solution path was submitted by Marc-Paul Lee, a long-time BEAM supporter who, unlike the theoretical mathematician who suggested this problem, knows how to approximate! :-D

And now, back to our original solution:

Now we know that Myriam must have deleted E, the digit in the ones place. So, our 4-digit number must look like ABCD. We also know that ABCDE + ABCD = 52713. We might think at this point that D + E = 3, but remember that just the ones place of D + E needs to be 3, so D + E could equal 3 or 13. We know that 0 <= D + E <= 18 (because D and E are 1-digit numbers so neither of them can be greater than 9) so D + E can’t equal 23, or anything else ending in 3 except 3 or 13.

Moving on to the tens column, we might think that D + C = 1 or 11, but is that right? If D + E > 9, then we will have to carry a 1, which means that D + C might actually be 0 or 10 and we would still get the 1 we need in our tens place. So D + C = 0 or 1 or 10 or 11. In a similar way C + B = 6 or 7 or 16 or 17, and B + A = 1 or 2 or 11 or 12. Finally, we know that A = 4 or A = 5.

Since A > 3, B + A (in the thousands place) can’t equal 1 or 2 (two of our options above). So, B + A = 12 or 11. Which means we carried a 1 to the ten-thousands place and A = 4 not 5.

So B = 8 or B = 7. If B + A = 12, then we didn't carry a 1 when we added C and B, so C + B = 6 or 7, but that’s not right because if B + A = 12, then B = 8. So B + A = 11, which means B = 7.

Now we know A = 4 and B = 7, and B + A = 11, which means we did carry a 1 from adding C and B, so C + B = 16 or 17. Thus, C = 10 or 9, but it can't be 10 because it is a 1-digit number. So C = 9.

Now we know that A = 4, B = 7, and C = 9, and C + B = 16. Because C + B = 16, we know that to get the desired 7 in our hundreds place, we must have carried a 1 from our addition of D and C. So D + C = 11 or 10. But because we know that C = 9, we know that D = 1 or 2, which means that E + D < 12. So E + D = 3, and we know that we didn’t carry 1 from our addition there, which means that D + C is not equal to 10, leaving us with D + C = 11. Plugging in C = 9, we can now find that D = 2 and E = 1.

Putting all the pieces together we get that Myriam’s original number, ABCDE, is 47921. And just to check, let’s do one last step: 47921 + 4792 = 52713.

Let's celebrate 𝜋!

Above: The first 54 digits of 𝜋 represented by colored discs. Design inspired by Martin Krzywinski’s 2013 Pi poster featured in the Numberphile video “Pi is Beautiful.”

Happy 𝜋 day! 𝜋 is probably the most familiar of the irrational numbers, and it represents a truly amazing mathematical fact: no matter what size circle you take, if you divide its circumference by its diameter, you always get the same number! That number, 𝜋, can be approximated as a fraction, such as 22/7, or a decimal, 3.14159…

The image above is actually another way to represent 𝜋. Instead of using digits, this image encodes 𝜋 in colors, where each of the numerals from 0 - 9 is matched to a different color.

A digit in the sequence of 𝜋 is then represented by a shaded disc, where the outside is the color corresponding to the digit itself, and the inside is the color of the digit that follows two decimal places later. The discs spiral from the outside to the inside, starting from the top left and moving right. The drawing represents a rich tradition of finding surprising beauty in mathematical randomness. The visualization was inspired by the work of Martin Krzywinski, which is featured in Numberphile’s video “Pi is Beautiful.”

It would be easy to overlook the richness and beauty embedded in 𝜋. The same thing can happen with math and mathiness. Sometimes, we’re quick to pigeonhole others and ourselves into convenient categories of math people or non-math people. It’s easy to decide what math should look like, or make assumptions about who looks like a mathematician and who doesn’t.

This 𝜋 day let’s take a step back from our preconceived notions. Celebrate the beauty and complexity of pi and of math, and remember that there's beauty and complexity in who is and who can be a mathematician, as well!

And if you’d like to celebrate 𝜋 Day with a little extra math, try out the challenge problem below. (The answer appears after the problem.)

Challenge problem: Jarek is bored in class and starts putting numbers on his paper like in the following pattern:

If he's really bored and keeps going with this pattern for a long time, what are the 8 numbers that will surround the square containing 1,000,000?

Bonus: What are the eight numbers surrounding the square containing 1,000,010?

Solution:

The numbers arrange themselves in squares. For example, 4 is in the top-left of a square containing the numbers 1-4, while 16 is in the top-left of a square containing 1-16, etc. There is a pattern of even square numbers going up and to the left, so because 1,000,000=1000^2, it is in the top left of a square containing the numbers 1-1,000,000.

That means that directly to the right of it, there will be the number 999,999, and directly to the left will be the number 1,000,001. That is when the pattern turns down, so below that is 1,000,002 (which is down-left from 1,000,000). So we've found three of the numbers around 1,000,000.

Down and to the right of 1,000,000, there will be the number 998^2=996,004 because another square finishes there. To the left of that (and right below 1,000,000) is 996,005.

Up and to the left of 1,000,000 is 1002^2=1,004,004. To the right of that (and directly above 1,000,000) is 1,004,003. To the right of that (and above-right of 1,000,000) is 1,004,002.

Thus, the eight numbers near 1,000,000 are 996,004, 996,005, 1,000,002, 999,999, 1,000,001, 1,004,002, 1,004,003, and 1,004,004.

Now, for the extra bonus. The number 1,000,010 appears nine spaces below 1,000,001 along the side of the square. Directly to the right of it is the number that is eight spaces below 996,005, which is 996,013. Directly to the left of it is the number that is ten spaces below 1,004,005, which is 1,004,015.

Above and below 1,000,010 are 1,000,009 and 1,000,011. Above and below 996,013 are 996,012 and 996,014. Above and below 1,004,015 are 1,004,014 and 1,004,016.

Thus, the eight numbers near 1,000,010 are 996,014, 1,000,011, 1,004,016, 996,013, 1,004,015, 996,012, 1,000,009, and 1,004,014.